Opening, April 9, 2024, 6 pm

Exhibition, April 10 – May 29, 2024

Long Night of Research, May 24, 2024, 4–11 pm

Huda Takriti: Who collected these photographs in this album—you or your mother?

Souheir Takriti: No, this was in an album for family photographs, but I replaced them and collected her work photos in one place.

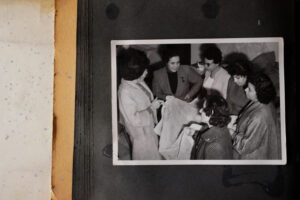

The beginning of a narrative is always of great interest for historical studies. It specifies what the story is about, as it distinguishes what remains anterior to and outside the narrative and what constitutes the core of the story. “Especially in the narrative reconstruction of conflicts,” says literary theorist Albrecht Koschorke, “the question of where to begin has decisive consequences, for the respective starting point is a kind of meter of the injustice inflicted on a conflict party, which legitimizes their resistance.”* Huda Takriti begins her three-channel installation On Another Note (2024) with the sounds of a rainforest and landscape details from the cover of a photo album decorated with Asian lacquer painting. Her mother, Souheir Takriti, keeps photos of her mother—Hikmat al-Habbal—in this album, which show her as a teacher and successful textile artist in Kuwait in the 1960s.

So my mother applied for an art teaching job in Kuwait to support her youngest brother. When she got the job, she took him with her to Kuwait to complete his studies there. In addition to her job as an art teacher at the school, she continued to work as a fashion designer, she designed some dresses for the princesses in Kuwait, where her older sister was already established.

On Another Note bears no immediate connection with the current tragedies in the Middle East. Rather, the artist lets us participate in a conversation with her mother about her grandmother. Souheir Takriti’s hands can be seen leafing through a photo album and holding textiles. We are witnesses to an attempt to be in the here and now with a deceased person, with photos and fabrics that serve as anchors for memories and narratives. We hear and read how a mother passes on her knowledge of past events to her daughter. A heritage becomes tangible, one marked by concern for the family in the face of Palestinian statelessness. On Another Note neither explains nor accuses. This filmic exploration through imagery and stories accesses a space that enables viewers to relate to the reality of Palestinian people in a very intimate way; people who have been forced to set out and start anew, over and over again, across generations.

These are some of the works she started and wanted me to continue as a memorial for her grandchildren, made together by her and their mother. She finished this piece, but the rest are still waiting for me to finish.

In this work, like her others on (post)colonial conflicts in the Arab world, Huda Takriti deals with historiography and memory and how they are conditioned by gaps. Sometimes, these gaps arise by chance. Often, however, they are owed to a different narrative that has prevailed due to unequal power relations or because material carriers of memories have gone lost forever as a result of destruction and displacement. By presenting her grandmother’s works as treasured objects to be protected and preserved, Takriti highlights the precarious existence of those whose rights are not safeguarded by citizenship.

Huda Takriti considers images and objects as so-called “actants” (Bruno Latour) that stake out—or transgress—the boundaries of what can be said and imagined about events. They herald what is not immediately before our eyes; they migrate into different contexts and are sometimes like uninvited guests who refuse to disappear from the public discourse. By listening to the stories of her mother and grandmother, by accepting her heritage and speaking to us with the images, patterns, and textiles handed down to her, the artist writes a “potential history” which, in the words of photography theorist Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, “does not mend worlds after violence but rewinds to the moment before the violence occurred and sets off from there.”** This history does not omit the violence of border crossings, migration registers, and strict citizenship laws. But at the same time, it also sheds light on those points in the past where the potential for a different, fairer world can be found.

In 1948, the British informed them that they had to temporarily leave Palestine for three or four days. They went to Lebanon and stayed in Tyre and Saida. As they crossed the Lebanese borders, they were considered to be Palestinian refugees.

In her work, Huda Takriti focuses on both highly personal and national narratives and the question of how they make the past tangible in the present. The artist explores the relationships between narrative and interpretation, between tradition and (re-)enactment, between original historical images and their functions in the present. By referring not only to documentation of past moments but also to processes which are not documented, the transfer of past events manifests as a complex, cross-generational process.

He participated in the 1936 revolution against the British mandate, as he was friends with Izz Addin al-Qassam.

Societies shaped by immigration would be well-advised to familiarize themselves with the formation of cultural memory and the corresponding perspectives and narratives. In German-speaking countries, for example, the name al-Qassam is usually associated with the missiles and brigades of Hamas. Palestinians, on the other hand, see this Syrian-Muslim preacher from the first third of the twentieth century as a leading figure against British and French mandate rule and an early opponent of Zionism. In 1936, he played an important role in events directed against the British mandate government, against Zionists and Arab elites, which—depending on one’s standpoint—were described as attacks, uprisings, general strikes or even as a revolt and revolution.

In this context, On Another Note can be seen as an intervention in the public discourse in Austria and Germany. For, in a post-migrant society, the memories of those who have come to these countries from elsewhere should become part of a shared memory culture. But the opposite is the case, as Palestinians rarely have the opportunity to present their perspective on the current asymmetrical war.

Velvet fabric is the only suitable material for this type of tufting. I noticed that the older frame started to break, and the colors of the work began to fade away. So I commissioned a carpenter to make a new frame for it. Because this work is made with a thin, fragile type of thread, we added glass to the frame to protect it.

In the exhibition Rewinding(s) In Rehearsal (2024) at Kunstraum Lakeside, the film installation On Another Note is presented with two works from the series Revisitation. In Three Acts. Act One, a digital photo collage on textiles, combines photos of Hikmat al-Habbal at her exhibition openings with film stills from On Another Note. In Act Two, vinyl shapes refer to the flipside of a photograph that also appears in the film and still bears the traces of the (other) album in which the photograph was originally placed. By appropriating the glass pane of the exhibition space as the back of a picture, Huda Takriti turns it into a (rehearsal) stage for photography. Upon entering the room, the inner foil shows the reversed flipside of this photograph. Like in the film, the artist interrupts the connection between what is inside and outside the photographic frame.

After a few months, they decided to go to Syria as the rest of the family was there and his brother was the mayor of the Salhiye neighborhood in Damascus. At that moment, they received a Syrian-Palestinian travel document and lived their entire lives as Palestinian refugees.

Before and within Kunstraum Lakeside, it takes a close and repeated look in order to grasp the essence of Rewinding(s). In Rehearsal. Visitors should mind their own point of view: Takriti’s exhibition not only has them witness this transfer of personal memories, it also situates this preservation of stories, techniques, and things partly in a (post)colonial regime of practices spanning from the issuing of passports to the photographic extraction and framing of specific moments.

With her exhibition, Huda Takriti gives people in a country that for decades saw migrants as “guests” who should go back home once their work is done, and whose stringent access to citizenship is still bound to this understanding, an idea of what it means to be stateless or a refugee; what it means when the ground is repeatedly pulled out from under one’s feet. The artist sees returning to past moments and recurring rehearsals as “a way of being with others differently—to act and interact in reciprocity, thus hosting and embodying one another.”

Huda Takriti (b. 1990 in Syria) lives and works in Vienna.

www.hudatakriti.com

* Albrecht Koschorke, Wahrheit und Erfindung: Grundzüge einer allgemeinen Erzähltheorie. Frankfurt am Main: S. Fischer, 2012. p. 63.

** Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism, London & New York: Verso, 2019, p. 28.

As part of

ÜBER DAS LAND / O DEŽELI

Jahr der Fotografie / Leto fotografije, 2024

www.ueberdasland.at

In cooperation with

![]()