Opening, July 4, 2023, 7 pm

Exhibition, July 5 – September 22, 2023

Works by Patrícia Almeida, Maria Anwander, Daniela Comani, Josef Dabernig, Claire Fontaine, Hermann Gabler, Hermann Gabler, Dora García, Irena Haiduk, Iman Issa, Ana Jotta, Marijn van Kreij, John Morgan, Kay Rosen, Hans Schabus, Lena Sieder-Semlitsch, John Stezaker, Mitchell Thar

Robin Waart was invited to develop an exhibition based on Kunstraum Lakeside’s bookshelf, an unsystematic library of artist’s and theory books accumulated since the founding of the space. Under the title Wörthersee, Wörtersee and in his double role as artist and artist-curator, he responds to the structures Josef Dabernig established for the Kunstraum with a site-specific intervention. Waart takes the specific presentation furniture, which all exist in pairs—provisions such as tables, chairs, partition walls, and shelves that characterize the technoid-administrative nature of the Kunstraum—as the starting point to address questions of duplication and duplicity, as well as concepts such as repetition, recognition, affinity, and friendship. “The gesture or idea informing my exhibition proposal is an intervention that draws from and even over-affirms Josef Dabernig’s architectural takeover. His design of the Kunstraum, which conditions everything that happens in the space, could itself be understood as an ironic-critical gesture and as a proposition for how something can be exhibited.” For Wörthersee, Wörtersee, the artist doubles the individual books in the library and traces Lakeside’s exhibition activities over the past twenty years in the form of a bibliography, which in turn appears as an artist’s book and artist’s poster. In addition to his own work, Robin Waart invites other artists, whether friends or colleagues he would like to collaborate with, to participate in the exhibition.

Robin Waart (b. in the Netherlands) lives and works in Amsterdam.

www.robinwaart.nl

Curatorial statement

Robin Waart

The double is not a pair, not a copy, an example, surrogate, or twin: passing, either in the place of or replacing, but what? An original, a first, second, something you do not see until you recognize. When there are two—not one—this is what happens: the thing that changes is perhaps not the thing but our relationship to it. And if “identity” is one such relationship of something or someone to themself, what was clear and (ac)countable becomes multiplied, supplementary, and impure. “Everything begins with Echo.”

One and one is eleven, but deliberately and intentionally so. “The day Hedwig came was a Monday, and that Monday morning, before my landlady slipped my father’s letter under the door, I wanted more than anything to pull the covers up over my face, the way I often used to do when I was still living at the apprentices’ hostel.” Yet another Monday, but a specific Monday when the protagonist in Heinrich Böll’s post-wartime novella The Bread of Our Early Years realizes he has forgotten who he was, what he looked like, what he did for a living: as if the present were all of a sudden past tense and the puzzle he was to himself a different puzzle altogether.

“One’s not enough, and two’s too much,” the girl he encounters that day says, hungry and undecided how much cake to order. “One and a half, then,” the waiter suggests. “Kann man das haben?” in turn, is her response—a German expression that is hard to translate here, implying something between “Is that possible?” and “Is that even allowed?”

Switching from the beginning to the end of a relationship: Annie Ernaux’s 38-page book The Young Man is the story of an alter ego “aborting” an affair with someone 20 years her junior, still “dans le premier des choses” (a phrase not meaning “in his prime” but rather “at the start of his experiences”)—while the narrator herself begins to see how “the present was for me but a doubled past” // “le présent n’était pour moi qu’un passé dupliqué”. The duplication, for her, turns to duplicity.

Wörthersee, Wörtersee looks at what doubling, pairing, splitting, juxtaposing, repeating something once (as the first step of repetition) can look like and which (instabilities) it can lead to, through the works of 18/19 artists. As much about translation as hesitation, to put a comma, a period, or not, Wörthersee, Wörtersee is an invocation (“Mirror, Mirror”), a warning (“Jacob, Jacob”), a sigh (“Love, love…”) of excitement or relief (“The sea, the sea!”). It is also an ongoing set of notes and my own attempt at making a bad copy.

Patrícia Almeida’s Mirror Ball (2008) is just that: a recording of the reflections cast back by one mirror ball, stuck in the constraints of a video screen. Shining back on the surroundings it is shown in—it pretends to have fragments of Lakeside in it, too.

Maria Anwander’s wall labels of Félix González-Torres’ iconic Untitled (Perfect Lovers) are extensions of the series My Most Favourite Art (2004–2009). Stolen or copied, these artifacts pointing to the (in)accuracies, typos, and typographies (like the missing accents in FGT’s name) take home what has to stay in the museum.

In Daniela Comani’s book project Neuerscheinungen (2009), instead of reissuing the same publication unaltered, the reimpression is used to update and regender the titles of those books we know all too well, and imagine for us a Mister Bovary, Doña Quixote, Little Princess, or Woman Without Qualities.

The Handschriftliche Kopien / handwritten copies that Josef Dabernig made from 1977 to 1999 do not replace reading with repeating: they interfere in the usual sense of order between manuscript and printed edition, after and before, multiple or unique. Scans of the copies themselves were published in book form again by BAWAG Foundation / JRP|Ringier in 2008.

Claire Fontaine’s Brickbats, by definition “pieces of brick used as a missile” or “critical comments or remarks”, are book covers wrapped around bricks, and, depending on how you look at them: bricks with a book cover around them—potentially smashing a window, changing your life.

The Chicago group exhibition OBST (2018) with the work of Hermann Gabler, Hermann Gabler, and Mitchell Thar is re-presented and re-produced at Wörthersee, Wörtersee with three different individual works: two paintings made by two different artists with the same name, one by Hermann Gabler (1908–1977), the other by Hermann Gabler. Mitchell Thar’s Untitled A2 (Groove) was made with the cover material from the artist book of the same title, cut down to the format of an A4 vinyl sheet.

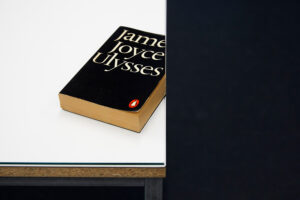

Dora García’s Ulysses (1999) is a copy (in the bibliographic sense) of James Joyce’s experimental novel with the top right corner cut off entirely, exposing the book’s insides, in some way as if every page has been dogeared and must be pointed to. Her Fahrenheit 451 is a reprint of Ray Bradbury’s novel, mirrored in its entirety, like the movie’s negative.

Irena Haiduk’s Proof of Siren(s) comes, in her own words, “in two classes: life size (approximately 142 × 106 × 19 cm, size varies for each view) and book size (19.5 × 24 × 13 cm), with aluminium hoods. […] The smaller Proof of Siren(s) must be hung with the crest of the hood at the height of the collector’s head. An edition of the book is placed on top of the hood.” This book is Seductive Exacting Realism, a monograph replicating (and camouflaging as) the missing volume no. 12 of Marcel Proust’s collected works in the Croation translation by Tin Ujević, which Haiduk acquired at a public auction in 2014.

Book of Fact: A Proposition (2017) by Iman Issa is an artist book with 78 figures: a bibliography, image credits, and index, but no images, documenting an exhibition that has never taken place—and never will. “It cannot be seen, for it is what causes seeing,” as the caption to Figure 73 states.

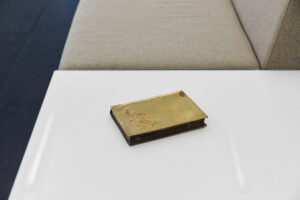

Ana Jotta’s Sem título (2017) is a bronze cast of a small, nameless book, itself destroyed in the making of a new original; recasting—between the lines—the poet Horace’s challenge to the medium of sculpture when he stated he had completed, in verse, a monument aere perennius, “more durable than bronze” (Odes III.30).

The work of Marijn van Kreij confronts repetition with its counterpart(s), using drawing as a touching stone to explore every side of it; its indifference to sameness, déja-vu, where it breaks and hiccups, like a song on repeat. His double drawings started when he tried to replace a work exchanged with another artist, to keep a copy for himself.

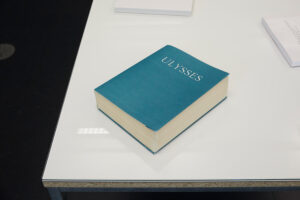

John Morgan’s Usylessly “duplicates the size, bulk and appearance of the 1922 Shakespeare and Co. edition” of James Joyce’s Ulysses (“Everything but the text.”). It is “the result of a close observation of the blue cover and form of the first edition” whose copies have, in time, become faded, brittle, and foxed.

In Kay Rosen’s Oh, Eau, punctuation is the protagonist: a micro-story in two parts whose meanings hover between love and despair, depending on where you put the commas, periods, or quotation marks. Oh, Eau exists as a vinyl wall text, dated with both the year it was made and the year it is shown (1989/2023), as well as a smaller letterpress print (1989/2018). Wörthersee, Wörtersee includes both.

Hans Schabus’ work invariably involves scale, whether it is his own height, that of a tree, or the world itself, reduced to something the size of a postage stamp. Turmbau zu Babel (2023) concludes a stack of puzzles he began making in 2010, exhibited with the unprinted bottom side up: on their reverse, an image of the biggest structure never built, outside of the paintings Bruegel made of it.

The two marbled curtains 25 Vorsatzpapiere mit rotem Kapitalband and 25 Vorsatzpapiere mit gelbem Kapitalband, which Lena Sieder-Semlitsch made for her installation at Kunstraum Lakeside, can be shown open and closed (like a book), referring not only to a cover or endpapers but also the story of Zeuxis and Parrhasius’ painting contest, about the truth in painting.

John Stezaker’s Double Shadow (2020) is from the same series of collages shown in his latest Double Shadow exhibitions, where two subjects seem to merge into each other’s backgrounds, intertwined, two-faced, and eerily indistinguishable from each other, even themselves.