Anette Baldauf

The turmoil started one day before the opening: On March 16, 2017 the art critic Jerry Saltz previewed the Biennial at the Whitney Museum, posting a picture of Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket and calling it beautiful. A trail of comments called the descriptor “beautiful” into question, as the painting referred to a black corpse disfigured by the violence of white supremacists. That same night the artist Devin Kenny posted a series of questions on Facebook addressing Schutz’s painting: “Who is the audience for this painting? […] What action is this work purportedly, and actually doing? Does it inform? Shock? Build connection? Help a new audience understand either emotionally or intellectually the complex set of factors all falling under the umbrella of white supremacy, sexism, and anti-blackness that led to this young person’s death?”1

The next day the Whitney Biennial opened with Open Casket on the wall in one of its rooms. On the painting’s canvas, thick and heavy brushstrokes spread brown, red, and yellow lines, hinting at the contours of a head enfolded by a bright yellow hallow. The knot of color in the canvas’ upper part was side-lined by a thinner and more figurative arrangement, suggesting a white, bottomed shirt and black jacket. While abstract in composition, the painting’s title left little doubt about its historical reference: the open casket funeral of 14-year-old Emmett Till in 1955.

One day after the Biennial’s opening black artists and activists initiated a vigil; they positioned themselves in front of Open Casket in an attempt to obstruct visitors’ view and protect the painting from an intrusive gaze. The artist Parker Bright posted videos that showed him taking off his coat in front of the painting and revealing a shirt that read “Black Death Spectacle”. Other artists joined Bright; quietly they placed their body next to him, or at points replacing him, in front of the painting. Then the artist and writer Hannah Black finally posted an open letter on Tumblr:

To the curators and staff of the Whitney Biennial: I am writing to ask you to remove Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket and with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum. As you know, this painting depicts the dead body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the open casket that his mother chose, saying, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways, not least the fact that this painting exists at all. In brief: the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.2

White ignorance and the politics of the white gaze

Black spelled out what artists prior to the publication of the letter had hinted at. In 1955 Emmett Till had been lynched by two white men in Mississippi. The Mississippi sheriff handed Till’s mutilated body over to his mother only on the condition that at the burial the casket would be closed. Mamie Till-Mobley refused to submit and called for a wide circulation of the photograph taken at her son’s open casket funeral. She wanted to “let the world see what I have seen […] The whole nation had to bear witness to this.”3 More than 600,000 people came to the funeral home to provide testimony to the brutal killing; and the news weekly Jet and the local Chicago Defender published the picture of his mutilated face.

In her essay The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning Claudia Rankine described Mamie Till-Mobley’s intervention as one that turned grieving into a public action: “Mobley’s refusal to keep private grief private allowed a body that meant nothing to the criminal-justice system to stand as evidence.”4 Following this line of thought, Josephine Livingstone and Lovia Gyarkye described Mamie Till-Mobley’s decision as a reversal of the visual regime that constitutes the terror of lynching. They write: “Although he was taken from her, the way lynched Americans were taken from their families, she was able to invert the final stage of public murder, which is spectacle.”5 In their argument Mobley’s invitation initiated a shift from spectacle to witnessing: The collective viewing of lynching consolidated Southern whites as a community in the name of white supremacy, now the image of the lynched body supported the coming together of black mourners. As Mobley’s intervention reasserted the community of the audience, it challenged the dominant gaze of voyeurism and recast the politics of morbid viewing into one of refusal and indignation.

It is often argued that the killing of Emmett Till marked a galvanizing moment in the history of the civil rights movement and that the photographs claimed as evidence of the terror on black lives played a major role in spurring the movement. As evidence of a US America that refused to desegregate, the photograph of Emmett Till haunted African-Americans for generations; innumerous songs, poems, artworks, and novels dedicated to Emmett Till testify the importance of his life, respectively his death.6 Because of this, the role of the photography and the narrative of evidence attached to it have been painfully ambiguous. In her essay “Can You Be BLACK and Look at This?”: Reading the Rodney King Video(s) Elizabeth Alexander writes: “The Emmett Till narratives illustrate how, in order to survive, black people have paradoxically had to witness their own murder and defilement and then pass along the epic tale of violation.”7

After the opening of the Whitney Biennial the vigil to protect the painting from the intrusive gaze of consuming voyeurs continued in the museum. “Wake work”, according to Christina Sharpe, is affective labor; it is the making of rituals to grieve and commemorate the dead and the relations to them. Sharpe lays out the different registers of “wake”—the path behind a ship, keeping watch with the dead, coming to consciousness—and traces the violence and pain as much as the strategies of survival in the face of Black negation. In the context of professionalized care provided by correctional facilities, wake work pays attention, tries to stand by and search for means of beholding each other.8 “Wake work is the work that we Black people do in the face of our ongoing death, and the ways we insist life into the present,” she writes. And with regards to the vigil to protect Open Casket she adds, “I think it’s really powerful that those Black young people put their bodies in front of that painting. For me, that is a wake. Those young Black people are keeping watch with the dead, practicing a kind of care.”9

Outside of the museum, Hannah Black’s letter moved the discussion into mainstream media, where it circulated mostly around questions of cultural appropriation and censorship. Critics accused Schutz of taking on what Greg Tate had called “everything but the burden”, in other words, to make use of black styles of music, dance, dress, slang, and now also the signs of suffering without having to confront the continuous terror that has defined black life in USA since the beginning of slavery.10 Schutz’s defenders argued that no group of people owned a particular subject or history, and that the claim to remove, even destroy, the painting was in line with the politics of National Socialism. As the discussion spread, Dana Schutz responded to Hanna Black’s letter in an interview with The New York Times.

I don’t know what it is like to be black in America but I do know what it is like to be a mother. Emmett was Mamie Till’s only son. The thought of anything happening to your child is beyond comprehension. Their pain is your pain. My engagement with this image was through empathy with his mother. […] Art can be a space for empathy, a vehicle for connection. I don’t believe that people can ever really know what it is like to be someone else (I will never know the fear that black parents may have) but neither are we all completely unknowable.11

Empathetic Identification: “I feel with/for you”

In the arts as well as in social theory empathy has often been claimed as a valuable resource of study. Within the vicinities of psychoanalytic theory it has been proposed as a means to make available unconscious material transferred from the subject of study to the researcher, allowing for a productive oscillation between participation and observation.12 But critics have also pointed out that as empathy is placed within the context of psychoanalysis it is equally built on an understanding of human nature, a universality of feelings, and, in many cases, the supremacy of the empathizing subject.

In social research referring to empathy suggests that however different the life of researchers might be, with the appropriate tools, they are able to find out how the subject of study feels and, equally important, put these feelings into words. But when empathy is delinked from any reflection on positionality—i.e. a reflection on who is talking and under which circumstances—it promises to bridge the gap between the researcher and the researched but often actually covers up the imbalance rather than work with and against it. “I feel (with) you,” says little about the relationship between the researcher and their subject of research, the cultural fabric and web of forces that connect those performing research and those upon whom research is performed. Because of this, it tends to foster dynamics of Othering and thereby contributes to the pervasiveness of so-called pain narratives in communities of marginalization. As bell hooks puts it in her critique of conventional ethnography: “No need to hear your voice. Only tell me your pain. I want to know your story. And then I will tell it back to you in a new way. […] I am still colonizer, the speaking subject and you are now at the center of my talk.”13 This is where “I feel with you” threatens to tilt into “I feel for you”: It puts the researchers’ emotional state at the center of the research process; it focuses on their pain as they feel for others.

In her book Scenes of Subjection. Terror, Slavery and the Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America this is an observation that Saidiya Hartman affirms in her analysis of white abolitionist accounts on slavery, arguing that in many ways their appeal to empathy makes the suffering of others their own. “The ease of empathetic identification”, she writes, “is as much due to (his) good intentions and heartfelt opposition to slavery as to the fungibility of the captive body”.14 As she recognizes the dualism of the spectacular nature of black suffering and the dissemination of suffering through spectacle, Hartman asks: “Can the white witness of the spectacle of suffering affirm the materiality of Black sentience only by feeling for himself?”15

Looking at Dana Schutz’s Open Casket, critics answer this question with “yes”. They see in Schutz’s claim to empathy an attempt to deracialize history. Banking on empathy, they argue, the artwork and the following statement did not engage in the affective labor necessary to articulate the multilayered relationship to and with an Other. This way of relating can hardly be considered part of what Tina Campt calls “reparative work”—it does not express a commitment to relationality and adjacency, an effort to place oneself in relation to and search for a language for the multiple components of the enduring history of dispossession.16 In other words, asserting empathy, the artist refused to reflect on how the killing relates not only to her position as a mother but also her own whiteness. And it might have made apparent another relationship to the killing, that to Carolyn Bryant, the white woman, who accused Emmett Till of harassment and who, 60 years later, confessed that the charges were fully made up. With regards to this constellation, Jared Sexton writes: “Schutz […] would like not to be like Bryant, implicated in the state-sanctioned racial violence against black people, and perhaps especially that violence which polices interracial sexual encounter.” And he adds: “She forgets that her interracial maternal empathy for Till-Mobley does not mitigate the fact that she is a white woman depicting a black boy killed, infamously, on the initiative of a white woman. Her empathy is entangled in that initiative.”17

The Whitney Biennial is not the only museum where community activists have recently challenged the invisibility of the white gaze and the relationship between ethics and aesthetics. In 2017 Walker Art Center took down Sam Durant’s interactive work Scaffold. Durant had built a massive sculpture to memorialize the 1862 hanging of 38 Dakota people 100 kilometers south of Minneapolis, but in the course of making a commemoration for the biggest mass execution in US history the artist and the art institution had failed to get in touch with local indigenous communities. After the opening, when protest spread and threatened to escalate, Dakota elders’ organized mediation and invited Durant and the Walker Art Center to search for a solution. Eventually, the latter acknowledged the elders insistence that it was the Dakotas’ responsibility to find ways to commemorate the killing without spectacularizing, re-victimizing, and re-traumatizing their history. In a collective ceremony the sculpture was dismantled and buried, with Durant agreeing to the destruction. Once he learnt that the Walker Art Center was built on Dakota land, Durant stated in an interview, he realized that “you couldn’t have a better test case of white ignorance in one place”.18

Similarly, but with less eagerness to learn and listen, the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Missouri found itself in a dispute over Kelley Walker’s exhibition Direct Drive. In the show Walker worked with digital images of the civil rights movement, police brutality against African Americans, and covers of KING magazine, many of them smeared with chocolate and toothpaste. At a public discussion in the museum the artist presented the formal elements of his artwork, dwelling on the disembodying potential of digital images. When members of the local community asked Walker to explain his own motivation, agenda, and possible audience in the light of recent police shootings in the city, the artist and the curator refused to engage and closed the discussion. In response, local artists called for a boycott of the exhibition.

Research Ethics

In recent years manifold interventions of black and indigenous scholars have shaken disciplines like anthropology and sociology out of their white comfort zone, forcing them to reflect on research ethics and spell out the relationship between white supremacy, coloniality, and ignorance. This irritation, scholars like Eve Tuck and Monique Guishard argue, is rarely the result of the wide introduction of ethical regulations that have started to define the rights of individual human subjects and the responsibility of academic scientists in Western academia. When Institutional Review Boards (IRBs) responded to the outrageous abuse of research in the context of National Socialism, for example, Tuck and Guishard write that the ethical regulations did not develop protocols on how to also disrupt the conditions of settler colonialism, scientific racism, and white supremacy. Most generally, their aim is to protect the institutions from claims of abuse.19

Because, as Norman Denzin put it, “ethics are pedagogies of practice”, ethics reflect social, political, and cultural structures within which they are located.20 To standardize these pedagogies, as it is proposed by IRBs, means often to universalize Western ideas. A set of guidelines directs behavior toward the observed; it aims to minimize harm introduced in the fieldwork. Such a perspective does not question the right to do this research in the first place, and it leaves untouched the many forms of violence that researchers can possibly do at a distance, in the course of description and interpretation of the so-called research subject.

In the 1980s feminist studies rigorously challenged the Western research ethos and science’s claim to systematicity, reproducibility, and value-freeness, but many black and indigenous scholars argued that their critique, too, was freight by the legacies of imperialism and its ethical dilemmas. Donna Haraway and Sandra Harding asserted the situatedness of research, posing partiality as a strength rather than a weakness of research. Knowledge is situated, Donna Haraway argued, because knowledge is related to a particular body, its emplacement, and according perspective.21 But whereas feminist scholars called into question the so-called outsider methodology with its assertion of objectivity and neutrality, scholars like Linda Tuhiwai Smith brought forth a set of more fundamental concerns: Famously posing that “the word itself, ‘research’, is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary”, Smith recalled the at best irrelevant and at worst destructive effects of research on indigenous communities. Moving from an outside to an inside perspective, she argues, does not necessarily level the atrocities legitimated in the name of “research”.22 For her, reflexivity with regard to the positionality of the research and the potential impact of the research on the researcher as well as the community have to be considered as core concerns of any research. In line with this claim, Junanita Sundberg suggests to let go of the supposed purity of an insider and instead focus on entanglement and complicity. Ethics, in her view, are better not understood as a means to eliminate dilemmas but, instead, a discursive field to negotiate the parameters of an accountable engagement.23

Doing Homework

Scholars dedicated to decolonization call this task—to scrutinize the historical circumstances and articulate one’s own participation and relationality in the context of pervasive structures of violence—“doing homework”. Following Gayatri Spivak, writers like Rauna Kuokkanen and Juanita Sundberg define the concept of “homework” as self-reflective work to be realized in relation to one’s own ontological and epistemological assumptions.24 It implies looking into the imperial foundation of Eurocentric knowledge production to reflect upon the violence that Eurocentric thinking established with regard to, for instance, what is rendered human and what not-yet fully human, nature, and culture. It also implies reflecting on the lingering alliance between, for example, empire and empiricism, the Cartesian subject and white supremacy, Enlightenment and individualism; and it also aims at a reflection on privilege, silencing, and epistemic ignorance. Learning to un/learn means first and foremost to unlearn privilege, Kuokkanen asserts, especially the privilege of endorsed ignorance that allows the perpetuation of silence about ongoing colonial violence.25 Doing homework also includes an honest confrontation with questions on one’s own motivation, aspiration, and desire in doing research. “The purpose of homework”, Juanita Sundberg concludes, “is to situate ourselves so as to enable ethical decisions about what to research, with whom, using which practices, and to what ends. Homework cultivates accountability for the epistemological and ontological worlds we enact through academic practices.”26

The painting Open Casket and its evolving debate suggest that Dana Schutz had little interest in doing this kind of homework. Schutz’s artwork and statements have contributed little to define white people’s adjacency to black suffering. While grappling with this relationship might open up a multiplicity of perspectives, it will necessarily also involve confronting the historical traces of a society once organized into those identified with humanity, liberty, and freedom and those always already bound to fungibility and accumulation.27

Looking back upon what the discussion on Open Casket did and did not do for anti-racism, Angela Pelster-Wiebe insists that what is needed is not some grand gesture but rather a series of ruptures in the daily routines that sustain white ignorance. In her own terms, for white artists to do their homework implies “learning to take your turn, putting in the effort to understand where the other person is coming from, apologizing when you get it wrong, knowing when to shut-up and just listen, and how to notice that someone else is being crushed under its burden, in need of another body to step up and take on that devastating weight themselves.”28

But unlearning white ignorance was apparently not an issue the artist was interested in working with and through. On the contrary, in the aftermath of the debate, art historian George Baker made the effort to place the contested painting within Schutz’s overall oeuvre. What he found made him muse over the significance of a self-portrait called Self-Portrait as a Pachyderm (2005). The oil on canvas painting shows big, bright, red hair wildly circling around the disfigured face of a woman in wrinkly, dark purple, black and brown skin, in other words, of a white woman in blackface.29

Moving Whiteness to the Foreground

Like empathy without reflexivity, becoming black is a prominent form of white refusal to engage with whiteness. Arthur Jafa’s The White Album (2018) captures the features of this escape route in a surgically precise and, for the white viewer, close to unbearable manner. For his video montage, Jafa develops a decisive black gaze and intersects found footage with video material shot of strangers as well as friends, who muse over the meaning of whiteness. Two years earlier, Jafa’s short film Love is the Message, the Message is Death (2016) had been appraised widely because of its affective take on the meaning of blackness. Citing the techniques of black music, the seven-minute film assembled at times beautiful, at times grotesque, comic, and devastating images of Black existence, soundtracked to Kanye West’s rap-gospel “Ultralight Beam”. Jafa himself asserted that he felt suspicious of the unison euphoric response to his film. In an interview with curator Apsara DiQuinzio he stated: “Even when people said, ‘Oh I cried,’ the very cynical part of my brain suspected some kind of arrested empathy with regard to the experience of black folk.”30

With The White Album Jafa’s aim was to again expand on the beauty and alienation of black music but now make empathy impossible. He wanted to stay with the black gaze but turn it upon what generally remains invisible or at least in the background (for the white subject): He focused on whiteness and switched from the quick editing of his previous work to allowing for a long, unwavering look at whiteness that assembled seemingly arbitrarily arranged portraits—the cell phone footage of a young blond woman getting lost in a string of platitudes on race; scenes from Oneohtrix Point Never’s music video “The Pure and the Damned” featuring an animated Iggy Pop; blurry surveillance footage documenting the arrival of a young, white man at a church and, 45 minutes later, his departure (leaving the filling of the time in between up to the viewer’s knowledge on what happed in the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina); video footage of a bearded white man pulling automatic weapons out of his many pockets; the video portrait of a preteen girl known as reality star Honey Boo Boo responding to accusations of “acting black” with “Ho, you can’t act a color! […] You can be a color, but you can’t act a color”. For 30 minutes—supposedly the film length varies depending on the special cut that Jafa makes for the different screenings—the film provides white viewers with no figure to identify with or feel empathy for; no safe space to retreat to or find comforting refuge. Like the Tourette-style compulsions of the handcuffed white man on the floor aggressively spitting the N-word onto the black police woman in front of him, whiteness comes to feel like a pathetic entrapment, a folly the protagonists continue to act upon despite knowing better and otherwise.

John Akomfrah described Jafa’s work as an investigation in “affective proximity”. Jafa puts together seemingly unrelated images and, similar to the techniques of a DJ, asks the viewer to pay attention to the space in between. Jafa calls this “black methodology”—for him, it is a work of relationality: “I’m trying to make a more complex embodiment of my relationship to these things, as opposed to just saying something that’s true or false about whiteness. I’m not interested in true or false, I’m interested in: this is how I’m feeling in relationship to it.” With such a radical openness, The White Album invites viewers, white viewers in particular, to join the labor of relationality. It asks (white) viewers to position themselves in relation to the images, and also the gap in between. As such it is a call for accountability—and a generously shared starting point for doing homework on and the un/learning of white ignorance.

Postscript: Second Take

In summer 2018, after the debate on Open Casket had left the mainstream media, the discussion briefly resurfaced with the appearance of a new painting exhibited at the LISTE Art Fair in Basel. There, Hamishi Farah’s painting Representation of Arlo (2018) featured in warm, pastel colors the idyllic scene of a young toddler, wild blond curls, and rosy cheeks, playing with a toy in his hands. Following the artist’s description, Representation of Arlo is a rendering of Dana Schutz’s son, allegedly based on a photo that he found on the Internet. At the art fair the painting did not stir much commotion, but when the German magazine Monopol called Farah’s work “revenge art”, an outcry of criticism made the magazine first add a black bar to the painting, covering the boy’s eyes, and eventually remove the image from the website.31 The painting, respective its photography, was criticized as a violation of Dana Schutz’s privacy, as no consent was provided for the making public of her son’s image. This outcry, Farah argued, was precisely the subject of his artwork: “The viewer’s response to the work creates the situation whereby they hopefully reach some point of self-reflexivity, regarding their responses to situations where white artists appropriate black bodies”, Farah was quoted saying. The white audience that Open Casket was made for looked at the painting and saw first and foremost an injured black body; then the same people looked at Representation of Arlo and recognized a child in need of protection from the public gaze. Ethics are pedagogies of practice.

Published in

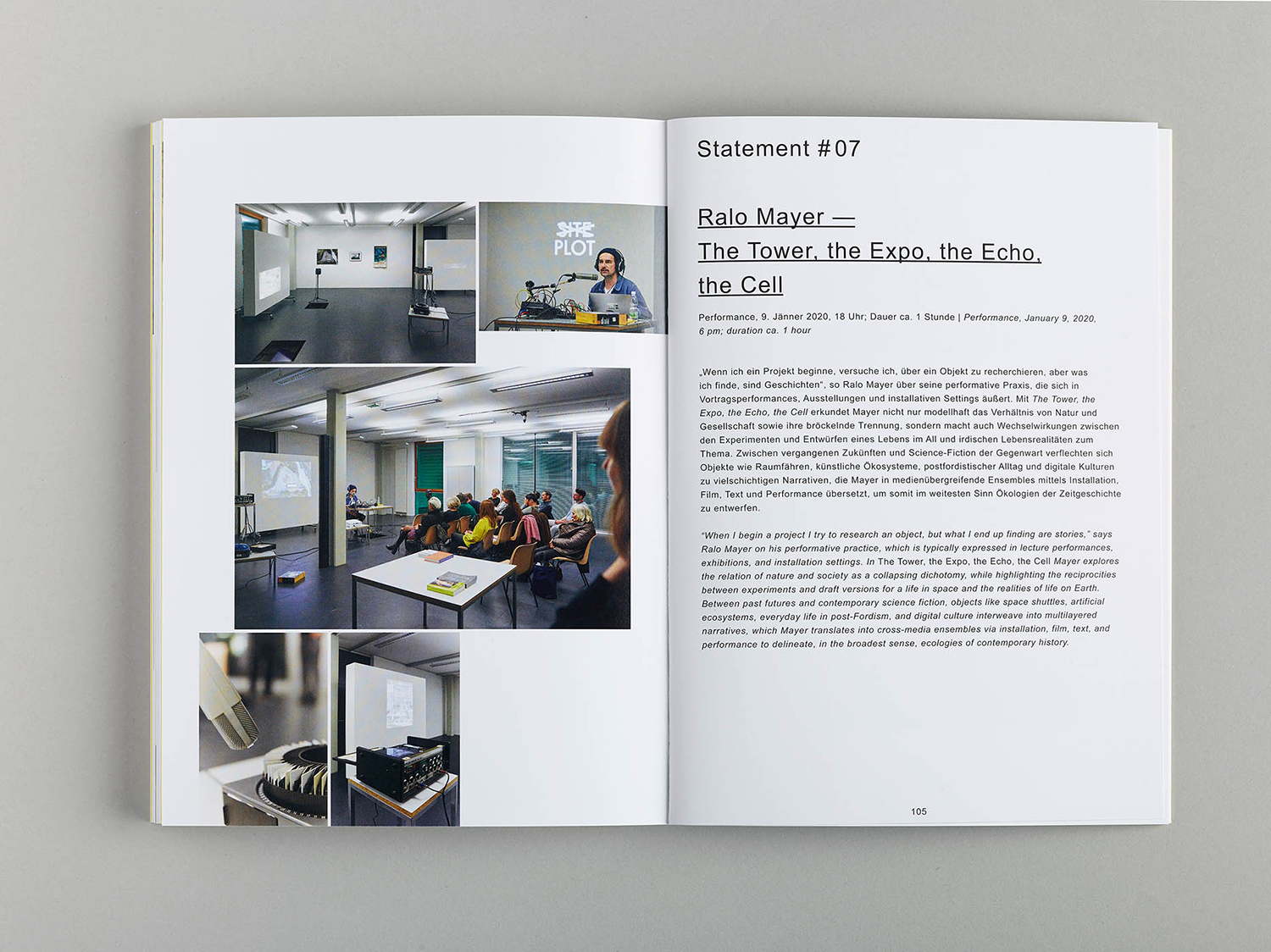

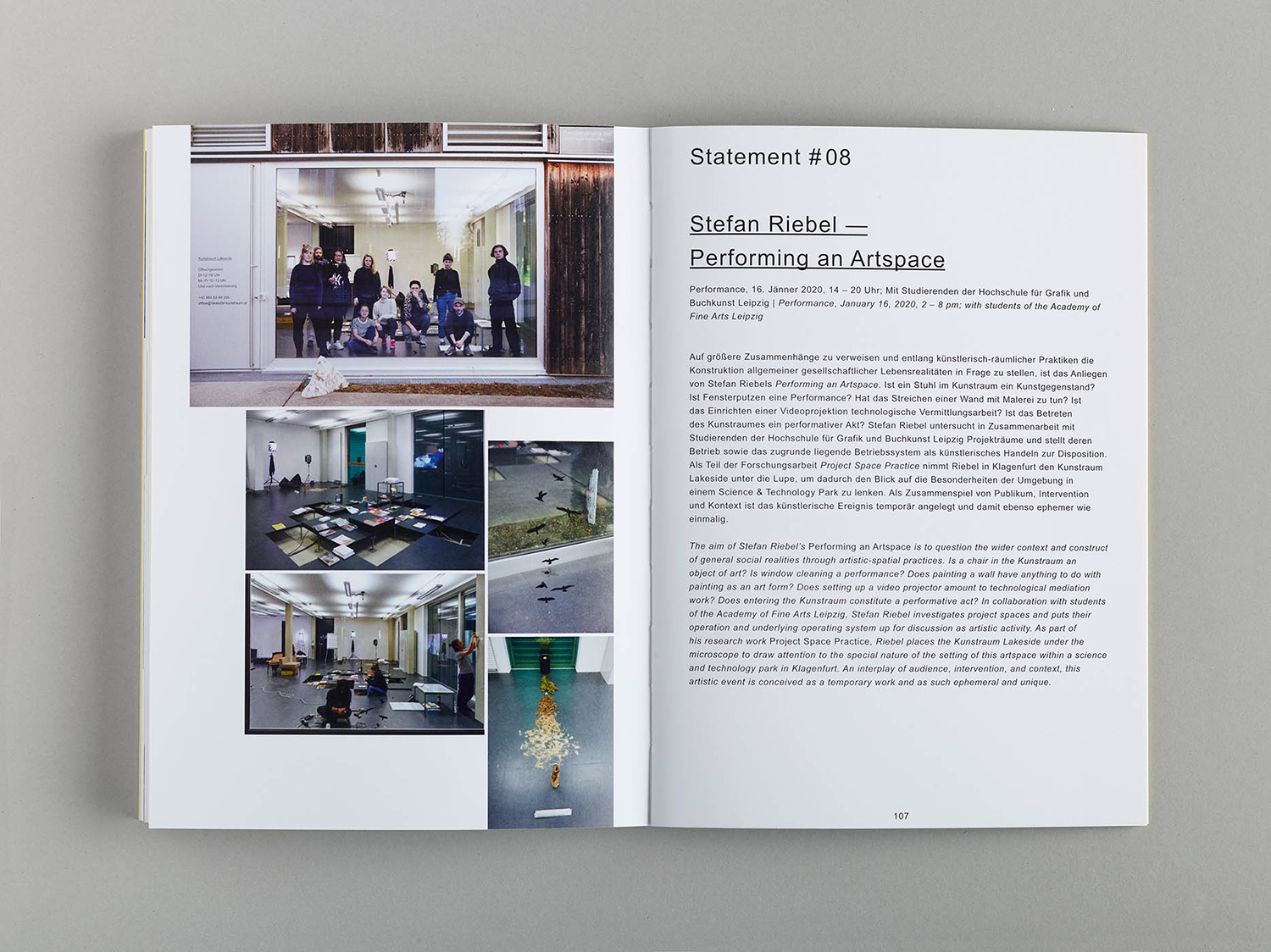

Franz Thalmair (Ed.): Kunstraum Lakeside — Prozess | Process,

Verlag für moderne Kunst: Vienna, 2020.

Download

1 Devin Kenny, Facebook, March 16, 2017, https://www.facebook.com/devinkk/posts/658751390060.

2 Scott W. H. Young, “Hannah Black’s Letter to the Whitney Biennial’s Curators: Dana Schutz painting ‘Must Go’,” eflux conversations, March 17, 2017, https://conversations.e-flux.com/t/hannah-blacks-letter-to-the-whitney-biennials-curators-dana-schutz-painting-must-go/6287.

3 Lisa Larson Walker, “The Problem With the Whitney Biennial’s Emmett Till Painting Isn’t That the Artist Is White,” Slate, March 29, 2017, https://slate.com/culture/2017/03/the-problem-with-the-whitney-biennial-s-emmett-till-painting-isn-t-that-the-artist-is-white.html.

4 Claudia Rankine, “The Condition of Black Life Is One of Mourning,” The New York Times Magazine, June 22, 2015, https://www.nytimes.com/2015/06/22/magazine/the-condition-of-black-life-is-one-of-mourning.html.

5 Josephine Livingstone and Lovia Gyarkye, “The Case Against Dana Schutz,” The New Republic, March 22, 2017, https://newrepublic.com/article/141506/case-dana-schutz.

6 Bebe Moore Campbell’s novel Your Blues Ain’t Like Mine, Toni Morrison’s play “Dreaming Emmett”, Gwendolyn Brooks’ poems, “A Bronzeville Mother Loiters in Mississippi. Meanwhile, a Mississippi Mother Burns Bacon” and “The Last Quatrain of the Ballad of Emmett Till”, or Audre Lorde’s poem “Afterimages”.

7 Elizabeth Alexander, “‘Can You Be BLACK and Look At This?’: Reading the Rodney King Video(s),” Public Culture 7 (1994): 77–94.

8 Cf. Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

9 Sharpe quoted in Siddhartha Mitter, “‘What Does It Mean to Be Black and Look at This?’ A Scholar Reflects on the Dana Schutz Controversy,” Hyperallergic, March 24, 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/368012/what-does-it-mean-to-be-black-and-look-at-this-a-scholar-reflects-on-the-dana-schutz-controversy.

10 Cf. Greg Tate, Everything But the Burden. What White People Are Taking from Black Culture (New York: Broadway Books, 2003).

11 Randy Kennedy, “White Artist’s Painting of Emmett Till at Whitney Biennial Draws Protests,” The New York Times Magazine, March 21, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/21/arts/design/painting-of-emmett-till-at-whitney-biennial-draws-protests.html.

12 Liz Bondi, “Empathy and Identification: Conceptual Resources for Feminist Fieldwork,” ACME. An International Journal of Critical Geography 2, no. 1 (2003): 64–76.

13 bell hooks, “Marginality as a Site of Resistance,” in Out There. Marginalization and Contemporary Cultures, ed. Russell Ferguson et al. (New York: Routledge, 1990), 343.

14 Saidiya Hartman, Scenes of Subjection. Terror, Slavery and the Self-Making in Nineteenth Century America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 19.

15 Hartman, 19.

16 Cf. Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017); Tina Campt at her lecture “Prelude to a New Black Gaze” at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, April 12, 2019.

17 Jared Sexton, “The Rage: Some Closing Comments on ‘Open Casket’,” contemptorary May 21, 2017, https://contemptorary.org/the-rage-sexton.

18 Carolina A. Miranda, “Q&A: Samuel Durant was pressured into taking down his ‘Scaffold.’ Why doesn’t he feel censored?” The Los Angeles Times, June 17, 2017, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/arts/la-et-cam-sam-durant-scaffold-interview-20170617-htmlstory.html.

19 Cf. Eve Tuck and Monique Guishard, “Uncollapsing Ethics: Racialized Sciencism, Settler Coloniality, and Ethical Framework of Decolonial Participatory Action Research,” in Challenging Status Quo Retrenchment – New Directions in Critical Research, ed. Tricia M. Kress, Curry Malott, and Brad Porfilio (Boston: The University of Massachusetts, 2013), 3–28.

20 Norman Denzin, “IRBs and the Turn to Indigenous Research Ethics,” Advances in Program Evaluation 12 (August 2008): 97–123.

21 Cf. Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–99.

22 Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples (London: Zed Books, 2012), 30.

23 Cf. Juanita Sundberg, “Ethics, Entanglement, and Political Ecology,” in The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, ed. Tom Perreault, Gavin Bridge, and James McCarthy (New York: Routledge, 2015), 120.

24 Cf. Gayatri Spivak, The Post-Colonial Critic: Interviews, Strategies, Dialogues (New York: Routledge, 1990).

25 Cf. Rauna Kuokkanen, “The Responsibility of the Academy. A Call for Doing Homework,”Journal of Curriculum Theorizing 26, no. 3 (2010): 61–74.

26 Sundberg, “Ethics,” 120.

27 Cf. Frank Wilderson, Red, White and Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

28 Angela Pelster-Wiebe, “White Artists Need to Start Addressing Supremacy in Their Work,” Literary Hub, August 29, 2018, https://lithub.com/white-artists-need-to-start-addressing-white-supremacy-in-their-work.

29 Cf. George Baker, “Pachyderm – George Baker on Painting, Critique, and Empathy in the Emmett Till / Whitney Biennial Debate,” Texte zur Kunst, March 29, 2017, https://www.textezurkunst.de/articles/baker-pachyderm.

30 Colony Little, “In ‘The White Album,’ Arthur Jafa Invents a New Film Language to Take on the Clichés of Empathy,” Artnet News, January 25, 2019, https://news.artnet.com/exhibitions/arthur-jafa-white-album-1448167.

31 Cf. Silke Hohmann, “Kunst als Rache. Künstler malt Sohn von Dana Schutz,” Monopol. Magazin für Kunst und Leben, June 15, 2018, https://www.monopol-magazin.de/kuenstler-malt-sohn-von-dana-schutz.